Transactional and relationship fundraising

Is there a difference between transactional and relationship fundraising, and if so what is it?

Some forms of fundraising are more obviously transactional than others; for example, undertaking a sponsored walk, ride, swim or other event, where the amount donated by individual sponsors usually relates to miles covered or peaks climbed. Or a given monthly contribution to an organisation which enables a specific outcome, such as a child being fed or treated for a particular disease, or a distressed or abandoned animal being saved. However, it could be argued that any form of fundraising has a transactional element to it, whether articulated (as in most cases) or not. Fair enough; we all want a reason to support a particular charitable cause and ideally to know what difference our gift will make. Whether our donation actually goes directly to enable the particular outcome advertised, or whether it is used in other more indirect ways, for example to fund (often necessary) administrative functions is a moot point but not one for discussion here. What is indisputable is that potential donors invariably need to know what the ‘case’ for supporting a particular cause is and therein lies the transactional element ‘if you give your support for …………..(this), then we will be able to do…………(that)’.

However, the problem with much charitable fundraising these days is an imbalance in transactional and relationship fundraising, with too much focus on the transaction and too little on the development of a relationship with donors or potential donors. A clever or attention-getting fundraising idea or proposition may elicit a one-off response but if you want a donor to support you on a continuing basis and at the higher end of their giving ability then you will need to win their trust, respect and goodwill and make them feel an inherent and important part of your organisation. That necessitates the building, over time, of a strong and enduring relationship. And it cannot be achieved simply by repeated requests for more, often at the same time as the organisation is thanking the donor for their last gift. A major part of the cultivation process is making donors feel that you as an organisation genuinely appreciate their involvement and are interested in what they think and feel about things, including your organisation, as individuals, not merely ‘donors’.

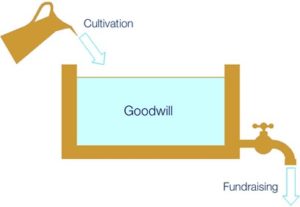

In considering transactional and relationship fundraising, it’s essential to identify that the primary motivation for a donor to give to a particular cause or need is goodwill, which is a finite commodity. If all a charity ever does is ask for money, there will come a point where it has exhausted the stock of goodwill with a donor, at which point donations will cease and are unlikely to recommence. Key to replenishing the stock of goodwill is the development and cultivation of a strong and enduring relationship that can only be achieved during a sustained period of not asking the donor for anything, especially money (the moment you ask for money it ceases to be relationship development and is simply another ‘ask’). Hence the concept of a ‘non-ask’ mailing, where charities deliberately refrain from asking for more money, but devote the mailing to explaining what it has done with the money donated last time, thanking the donors profusely and, ideally, inviting them to visit the charity personally to see what their generosity has achieved at first hand. Sadly, many charities seem to think ‘non-ask’ mailings are an expensive ‘lost opportunity’ without bothering to calculate how much more they will raise next time round from a strong and rejuvenated relationship.

The key point for charities to bear in mind is that, ideally, the development of a relationship comes first and is an ongoing process which over time is strengthened, so that it in effect becomes the continuum within which periodic fundraising requests are made. While those fundraising requests in effect tap the reservoir of goodwill, this is replenished by the ongoing process of cultivation. In its absence the stock of goodwill will inevitably become so depleted that future fundraising efforts fail. However, implemented effectively a cultivation programme should over time result in the development of a sustainable core of donors, who from giving the occasional donation, progress to become regular supporters and, if their financial circumstances permit, donors of (very) substantial amounts. Historically, and with few exceptions, major donors to an organisation have usually been previous supporters, often at a much lower level, who see their relationship with that organisation develop to a level where they are happy to make a major gift. Similarly, donors of legacies, which statistically tend to be at substantially higher level than the majority of life time gifts, invariably have developed an enduring relationship with the organisation (and vice versa) over a period of time, often many years.

Ken Burnett recognised the need to focus on relationships in his 1992 book Relationship Fundraising, but while he is credited for inventing the process the fact is that he did not – he simply drew attention to it. In reality, relationship fundraising has been around since at least the middle ages and the Church of England was an enthusiastic and highly effective proponent, persuading many wealthy landowners of the benefits of bestowing their patronage on local churches in return for appropriate recognition (for which read ‘cultivation’) by the Church itself. Whether the Church of England has lost sight of the value of maintaining and developing relationships with current and potential donors is perhaps a relevant question today. Unfortunately, many of today’s charity fundraisers have either forgotten the lessons highlighted in Burnett’s book, or have never read it. If not, that would be a good place to start!